Foreword

My introduction to border issues began in 1990. I was a member of the Douglas County Board of Commissioners in Nebraska when I was asked to serve on a United States Trade Representative (USTR) advisory committee to assess the impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on local and state governments.

I am fortunate to have developed lasting friendships in Mexico from these early experiences. Following my work with the USTR, I traveled regularly to Mexico as a senior executive at Archer Daniels Midland (ADM). During that period, I traveled to Mexico with few concerns about my personal safety. That would change.

In 2004, my interest in understanding illegal migration across our border prompted me to travel the roughly 115 miles southwest from the U.S. border town of Nogales, Arizona, to Altar, Mexico, in Sonora, a trip I would never attempt today. I had read reports that up to 5,000 people a day were crossing through the border area close to Sasabe, but that their journey began in Altar. It was a risky trip, but I wanted to assess the situation for myself. It immediately gave me a different perspective on the precarious security situation in this particular region of Mexico. That night in Altar, I went to bed listening to gun shots and women screaming; throughout the night, there was unidentified pounding on my hotel room door.

I took my first photo of the border fence in 2005, when there were still many areas that did not have fencing. Much of the fence that did exist then was constructed out of discarded military material. In 2019, I flew the entire U.S./Mexico border to better understand the geography along the border.

The next morning, we attended a mass at the local church that was held regularly and intended for people who were preparing to cross the border. Later, we walked through the streets, watching as people bought backpacks, shoes, clothing, water and food, all in preparation to cross between ports of entry from Mexico into the U.S. We stood in the town center as people negotiated deals and money changed hands with “coyotes,” who gave instructions to their new “clients” on when and where to meet. We also visited the designated “stash” houses where people waited for their names to be called to take the next step in their journey north. Some had been waiting for days. We got yelled at, chased out of houses and threatened, but I managed to get a few photos along the way.

Then we prepared to do the math. We parked in the middle of town, and we watched people being crammed into vans. The traffic picked up in the late morning so that everyone could be staged at the border and ready to cross by dark. We counted an average of 25 people per van. Then we left town and followed some of the vans. We stopped after about 30 minutes of driving and stayed in one location to count the vans: between 35 and 40 vans per hour. It added up to roughly 5,000 people a day being moved from this small town to the border.

We then followed the vans to a place called the “Brick Yard,” so-named because of its historical use for manufacturing bricks, now used as the final staging area for people crossing. We sat watching the activity from the relative safety of our vehicle. It was organized chaos. There were so many people it was difficult to know who or what to focus on. Young women wore high heels and makeup, looking more like they were going to the movies or on a date rather than getting ready to make perhaps the most dangerous trip of their lives. Mothers cradled babies and comforted young children. It was a challenge taking photographs because I had to keep my camera concealed. Eventually, everyone was rounded up and squeezed into the beds of pickup trucks equipped with livestock panels to keep people from falling out. They were driven to the border, dropped off and left to wait in different areas for darkness to fall and their opportunity to cross.

The Brick Yard meant different things for the people who congregated there. For some, it represented the promise of freedom and safety; for others, it was the chance to fulfill an economic dream; and for too many, it meant the continuation of a life of suffering, marked by forced labor, rape, exploitation and even death. People came to this place to escape their old lives and run to what they believed to be a better future across the border in the U.S. They brought with them their faith, but they could not possibly know what fate awaited them on the other end of the journey.

Those were my early, first-hand experiences with what most Americans today imagine when they read about America’s “immigration problem.” There is nothing new about people crossing borders illegally, neither in the U.S. or anywhere around the world. I have photographed border issues around the globe, in Italy, Eastern Europe, several African countries, Colombia, Central and South America. It is an emotionally charged issue for the people crossing and for the people living in the countries receiving those who are migrating. In many places, immigration has provoked hostility. In 2005, I traveled to several cities in the U.S. to document the protests when the immigration debate here at home erupted in the streets of major cities. We often feel the moment we are living in is unique, but immigration to North America, and resistance to it, has spanned centuries.

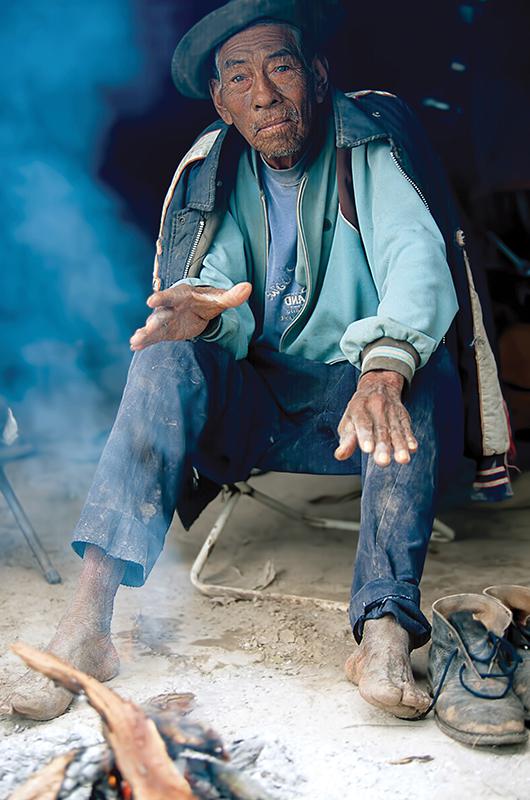

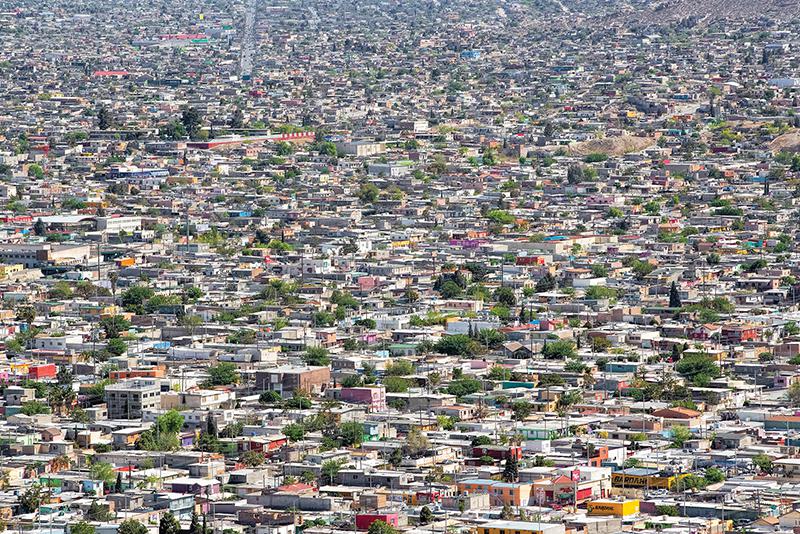

In 1995, when traveling to Mexico for business, I began to document the living conditions of local residents. At the time, it was estimated that 65 percent of the Mexican population was living below the poverty line, with 35 percent living below the extreme poverty line.

In 2005 and 2006, the immigration debate became more heated and political, and children were caught in the middle. Here, a young girl waves a flag at a rally in El Paso, Texas. Her shirt reads, “We are not the enemy. We are part of the solution.”

America's Immigration History

Our “modern-day” immigration began in 1492 when the first European explorers arrived. The first permanent colony was established in 1607, and throughout the 1700s, large numbers of Europeans came to America. During the mid-1800s, Irish immigrants fled the potato famine. Later in the 1800s, Chinese workers immigrated looking for work. In the early 1900s, many immigrants arrived from Southern and Eastern Europe as well as from Mexico to work in mines, in agriculture and for the railroad as the western United States began to develop. During World War I, the demand for Mexican labor increased, while during the Great Depression, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans were deported. By some accounts, half of those deported were U.S. citizens.

During World War II, the U.S. reversed course again. Labor shortages in 1942 led to the creation of the Bracero Program, and over the subsequent 22 years, more than 4.5 million contracts were signed to allow temporary Mexican workers to legally enter the U.S. In 1964, the U.S. government canceled the Bracero Program because it was perceived to be adversely affecting the wages and employment opportunities of U.S. workers. Both federal and state governments continue to implement laws to influence immigration. In 1994, California passed Proposition 187 which denied healthcare, education and welfare benefits to undocumented immigrants. Courts struck it down because the federal government has the exclusive authority and responsibility to regulate immigration. Other states have modeled legislation on Arizona’s SB1070, which asked local law enforcement agencies to enforce federal immigration law. Again, because immigration is the exclusive realm of the federal government, courts have struck down many such state provisions. A key Supreme Court ruling in 2018 allowed many people to be held in immigration detention without bond hearings. The many different policies and court interpretations of immigration law and policies deliver inconsistent messages to the public and may make fair and just enforcement of the laws more challenging.

Many of today’s major immigration challenges echo past debates and history. The first major anti-immigration movement in the U.S. was directed at Germans and Catholics in the 1850s. America’s long and varied immigration history includes a wide range of ethnicities, languages, cultures and religions. Immigration debates over our southern border have had their own unique history, including significant changes in the demographics and the dynamics of who is coming across and why.

Traffic into the U.S. in the past decade has shifted from mostly Mexican adult males looking for work to unaccompanied children and families from Central America seeking asylum. This will continue to change. More recently, an increasing number of Mexicans are fleeing cartel violence at home. Each group that arrives has a different impact on our country. While some U.S. industries would be crippled without access to foreign-born labor, the increasing numbers of unaccompanied minors, family units and asylum-seekers have exposed huge weaknesses in our immigration system. The current backlog of immigration cases is estimated at close to one million. A person who crosses into the U.S. seeking asylum or who is apprehended between ports of entry can wait up to four years or longer to have their case adjudicated.Complicating matters, it is estimated that about half of undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. are people who arrived here legally but overstayed their visas.

To better understand these migration flows and dynamics, our Foundation began purchasing property on the border with Mexico in Arizona and Texas beginning in 2011. I like to say that the intervening years and experiences have given us a graduate-level education on border issues that we could not have acquired any other way. While there is no substitute for seeing and experiencing the border and its related issues first-hand as we have, the photos I’ve captured over these many years and compiled in this book are an attempt to convey, through images, what we’ve learned.

As the immigration debate heated up yet again during the 2018 midterm elections, I decided to fly over and document the entire U.S./Mexico border by helicopter, covering most of the distance multiple times. The section entitled The Border is a result of these flights, and the photographs are in sequential order from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. We’ve also created a multimedia experience using these photographs and others at www.50borderstates.com.

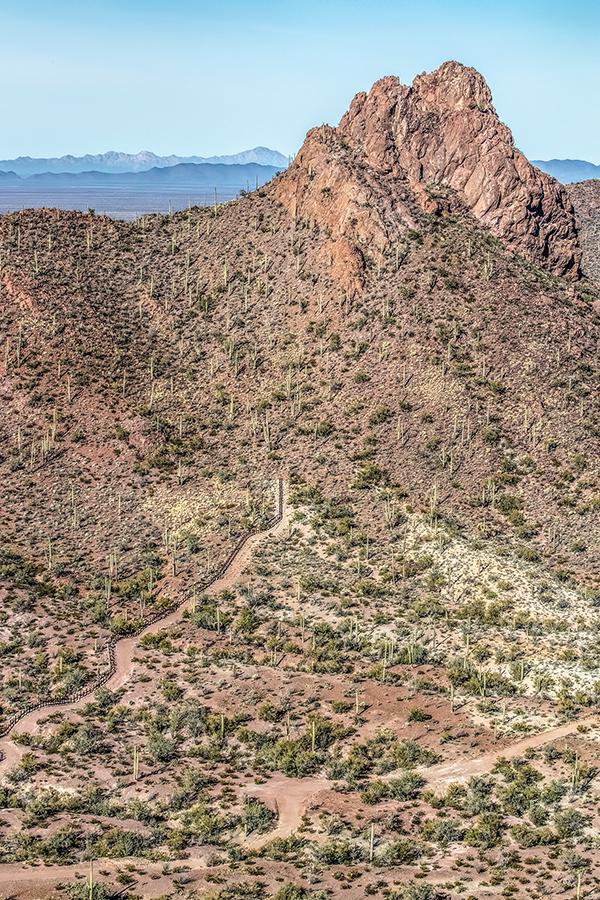

There are three things that I think any person would conclude from flying along the entire border between the U.S. and Mexico. First, there are areas so rugged and desolate that no human being would attempt to traverse them, so there is no need for a border barrier in these areas. Second, the huge expanse of land cannot be adequately described in words. And third, our border has some of the most beautiful lands and wildlife in America.

These three photos are of the same hill located in Mexico, directly across from our ranch in Arizona.

In this photo (looking from the U.S. side of the border), you can barely make out the structure on the top of the hill.

These three photos are of the same hill located in Mexico, directly across from our ranch in Arizona.

This image was taken from a helicopter and is more recent. It shows what is remaining of the shed after the Mexican military burned it down.

These three photos are of the same hill located in Mexico, directly across from our ranch in Arizona.

This image was taken from a helicopter. It shows a cartel scout and a tripod used for his scope. This scout helped to direct drug traffic crossing the border and assisted mules in trying to avoid apprehension by law enforcement. With the destruction of this shed, the scouts will simply relocate to another position or rebuild in the future.

People can easily hide in the terrain and vegetation of the Southwest’s high desert. These two photos have four men hiding in the brush, illustrating how easy it is to go unseen. This photo shows flags the men are holding up, signaling their location in the brush, though you cannot identify the people. The bottom photo shows the men standing.

People can easily hide in the terrain and vegetation of the Southwest’s high desert. These two photos have four men hiding in the brush, illustrating how easy it is to go unseen. The top photo shows flags the men are holding up, signaling their location in the brush, though you cannot identify the people. This photo shows the men standing.

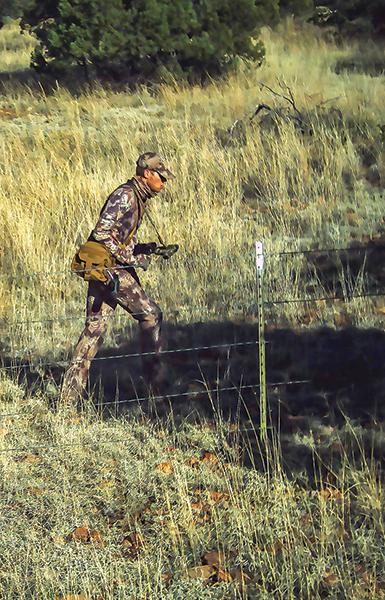

We have experienced several “walk ups” on our ranches. This photo shows a man wearing camouflage pants and booties. The booties make it more difficult for Border Patrol to track a person. Our ranch manager gave him dinner while he waited for Border Patrol to pick him up.

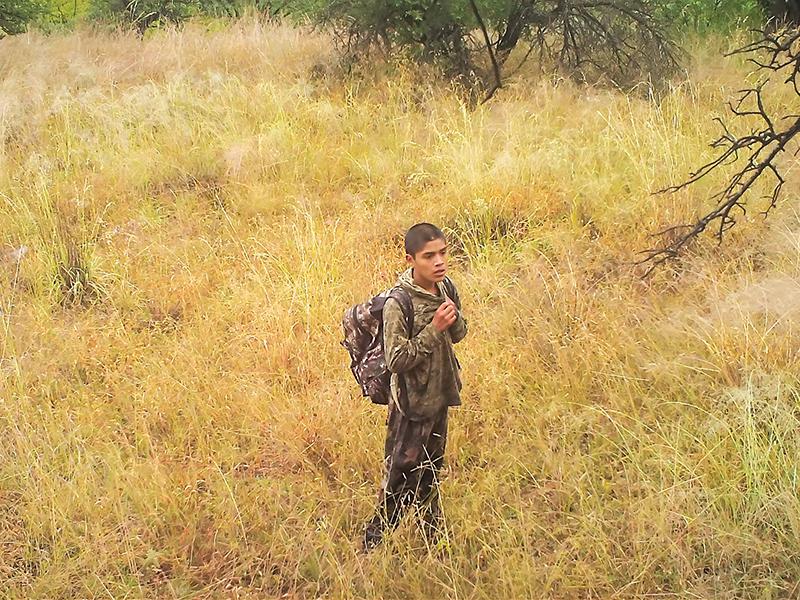

On our other ranch, a young man approached our property just before sunset. His clothes were dirty and ripped, he was freezing, yet drenched in sweat, and he was scared. Something had happened to him while crossing, but he wouldn’t tell us what. The temperatures that evening fell to below freezing; if he had not found us, he might not have survived the night.

The Cross Border Drug Trade

The migration of people is what grabs the headlines, but the story that I believe to be the most important and underreported is how narcotics cross our border and contribute to over 93,000 reported overdose deaths in our country annually. The number of U.S. citizens dying every year from drugs brought across our border exceeds the number killed in car accidents and gun violence combined, and accidental overdose is the leading cause of death for those under 50. To put this into perspective, drug overdoses kill Americans at a rate equivalent to having a 9/11 attack every other week. The recent increases in drug overdose deaths have reduced average life expectancy in the U.S., something that has not occurred since World War II. A large amount of these drugs come through our southern border, both through legal ports of entry and between ports of entry.

People are most familiar with the opioid epidemic occurring across our country. However, that is only part of the story. Cocaine, benzodiazepine, methamphetamine and overdoses from synthetic drugs have all increased in recent years, while fentanyl overdoses have skyrocketed. Fentanyl is often referred to as a drug of mass destruction because small amounts can kill thousands of people. The numbers you do not see are the hundreds of billions of dollars lost to drug addiction, healthcare costs, lost wages, lost productivity and lost lifetime earnings from the people who overdose or remain with a substance abuse problem. What can’t be measured is the pain that families endure from watching loved ones suffer from addiction.

Narcotics flow across our southern border at unknown rates. We measure successful enforcement in terms of drug seizures, but these numbers do not reflect what officers fail to interdict. Once across the border, these drugs flow through efficient and pervasive networks that reach every community in the country. The farther the narcotics move from the border, the more difficult it is to stop them. Law enforcement requires an array of tools to succeed against the well-resourced criminal organizations profiting from the distribution of these drugs. In their home countries, these organizations brutalize their own citizens and use violence as a way to operate with impunity. Innocent people on both sides of the border suffer. Mexico is now considered the second most dangerous country in the world. This is not what we want for our neighbor, but as long as American demand for narcotics remains high and continues to increase, we will continue to contribute to this violence.

Drug use has become so prevalent across the U.S. that in some cities people shoot up openly on the streets. In this photo in downtown Philadelphia, one man is shooting heroin as the other man prepares his syringe.

Central America’s Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) have the geographic disadvantage of being on the route for drugs that are being trafficked up through Mexico, along with their own domestic challenges of extreme poverty and endemic gang violence. There is no way to protect international borders when such a disparity of safety and wealth exists between countries, especially when criminal organizations and gangs operate with impunity. In many cases, right or wrong, our country has become the destination of hope. The United State’s system of government and its enforcement of laws is a large part of the hope people are seeking when they cross our border. In their home countries, the rule of law is frequently absent, allowing criminal activity to flourish. Yet keeping our own system functional requires knowing who is entering our country and why.

As immigration traffic increases between ports of entry, it requires additional attention and resources from Border Patrol, which inevitably distracts Border Patrol from drug interdiction efforts. This allows transnational criminal organizations to take advantage of the diminished security and move drugs into our country more easily. In many areas, every mile of border has different characteristics. Some areas are so remote, it can take hours for Border Patrol agents to reach them. In other areas, fences make it more difficult for criminal elements to blend into an urban population. In places like Big Bend National Park in Texas, or in Arizona west of Nogales, nature has already provided an effective barrier in the form of canyons and mountains. It is a complex and ever-changing challenge.

In 2005, on a helicopter flight, we spotted two men on horseback crossing the border into Arizona from Mexico. They had large burlap bundles strapped to the sides of their horses, which likely contained either marijuana or cocaine. When they saw our helicopter, they quickly turned back into Mexico.

Border Enforcement

The challenge of border enforcement is not new. In 1915, the United States Congress authorized “mounted inspectors” to prevent illegal crossings from Mexico into the U.S. In 1918, the first border fence was erected in Nogales, Arizona. In 1924, Congress officially established the United States Border Patrol. It took another 90 years, in 2006 under President Bush, for Congress to authorize significant additional border fencing: 700 miles of new fence under the Secure Fence Act.

During Border Patrol’s early history, the U.S. military would assist along the southern border. During the Mexican Revolution in 1910-1920, 20,000 U.S. Army soldiers monitored the border to prevent violence from spilling over into the U.S. In the late 1920s, the U.S. Army’s role at the border diminished. In 1950, the U.S. Attorney General requested the U.S. Army support Border Patrol with the deportation of Mexicans following the end of the Bracero Program. The U.S. Army rejected his request. In 1982, the Defense Authorization Act allowed the military to expand its ability to assist federal law enforcement agencies. This support was further increased with the passage of the 1989 Defense Authorization Act, which expanded the military’s role in the War on Drugs. In 2001, after the attacks on 9/11, the Department of Defense stepped up its role in supporting counter-narcotics and counterterrorism efforts at the border. The military’s role in border enforcement is restricted by law, but every president since Ronald Reagan has requested some troops to assist at the border. These troops are deployed for a number of reasons, including identification and interdiction of suspected transnational threats; supporting Border Patrol with air reconnaissance or ground surveillance and monitoring posts; medical evacuation; sensor operations; vulnerability and threat assessments; engineering and construction support for barriers, lights, roads and bridges; and drug interdiction efforts. Often the current debate over our southern border and immigration policy seems to ignore or shortchange this varied and complicated history.

New Markets For Criminal Organizations

Current events that will become a future chapter of border enforcement history are playing out quietly behind the scenes in a way that could have significant consequences for our country. Our domestic policy decisions to legalize marijuana are providing Mexican cartels with new business opportunities; the best example of this is can be found in California. In November of 2019, an El Dorado County deputy was shot and killed by several Mexican nationals involved in an illegal marijuana grow. His death is a direct outcome of the changing landscape of illicit drug production and distribution as our drug policies change here in the U.S. This violence is escalating every year.

The legalization laws in California have allowed illicit production of marijuana to blend with the legal marijuana industry, essentially enabling the black market to increase and hide in plain sight. It is estimated that less than 20 percent of the marijuana produced in California is consumed in California. Legally produced marijuana is prohibited from being transported out of state, so marijuana leaving California is from illicit production, often by Mexican cartels that have moved operations across the border. According to the New York Times, the black market for marijuana is actually increasing, well into California’s second year of legalization.

U.S. legalization has encouraged Mexican cartels to relocate a significant amount of their marijuana production from Mexico into the U.S. and to convert marijuana acres in Mexico to poppy production. The DEA reports that Mexican poppy production increased by 35 percent between 2016 and 2017. During that same time period, the Mexican Army discovered and destroyed 26 percent more farm land growing poppies while land found growing marijuana dropped by 24 percent. Most producers in Mexico are poor farming families that face a clear but harrowing choice: grow what the cartels demand and survive, or resist and be killed.

In Governor Newsom’s 2019 State of the State address, he called for National Guard troops to “boost the National Guard’s statewide Counterdrug Task Force by redeploying up north to go after illegal cannabis farms, many of which are run by cartels, devastating our pristine forests.” As I flew over hundreds of illicit marijuana grow sites in northern California (pictured on right), it reminded me of flying over areas in Colombia where farmers had carved out sections of forest to grow coca to produce cocaine.

A warrant served in northern California in 2019 provided access to over 1,200 live plants and almost 1,000 pounds of processed marijuana.

The Associated Press reports that industry analysts estimate $3 are spent in the illegal market for every $1 spent in the legal market. This estimate is supported by reports from CNN stating that $8.7 billion of the $12 billion marijuana market in California is from illicit production. As revenue from legal marijuana drops in California, the California Cannabis Industry Association notes that, “widening the price...gap between illicit and regulated products will further drive consumers to the illicit market at a time when illicit products are demonstrably putting people’s lives at risk.”

A warrant served on an illegal marijuana grow in California in 2021 demonstrates the chemicals used that negatively impact the environment and public water sources.

As deputies serve a warrant, people scatter. It is common to have several grow operations in close proximity of each other. By the time we reached the last site, everyone had made a quick exit, leaving behind weapons, marijuana and cocaine that was arranged in neat rows, ready to consume.

As deputies serve a warrant, people scatter. It is common to have several grow operations in close proximity of each other. By the time we reached the last site, everyone had made a quick exit, leaving behind weapons, marijuana and cocaine that was arranged in neat rows, ready to consume.

The shift in illicit production in both countries is reflected in the amount and mix of drugs interdicted by law enforcement agencies. Between 2014 and July 2021, marijuana seizures at the U.S./Mexico border dropped by 90 percent (from 1.9 million pounds to 191,071 pounds) while heroin seizures at the border increased by 268 percent (from 1,904 pounds to 8,093 pounds) and heroin seizures across the country increased by 870 percent. Between 2018 and July 2021, fentanyl seizures at the U.S./Mexico border increased by 325 percent while fentanyl seizures across the country increased by 273 percent.

Market forces are behind this shift. Cartels earn higher profits by producing marijuana in the U.S. for three reasons. First, there is a reduced transportation cost; second, the risk of losses from drug interdiction efforts compared to bringing product in from Mexico is lower; and third, cartels can replace marijuana acres in Mexico with poppy acres. Poppy production is more profitable today thanks to the market demand created by the epidemic of opioid addiction in the U.S. and the resulting crackdown on opioid prescriptions. Mexican cartels now provide over 90 percent of the heroin coming into the U.S., an increase from 10 percent in 2003.

As the legalization of marijuana in the U.S. helps drive a larger “black market,” the impact on the environment, the physical landscape and public safety cannot be understated. Marijuana production in national forests has poisoned wildlife and polluted water sources. According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the seizures of illegal marijuana crops in wildland areas more than doubled in 2018, the first year that marijuana was legal in California. Illegal grows litter the countryside, some deep in the forest, others out in the open. Along with these grows come large amounts of trash, pesticides, soil erosion and water contamination. The number of illegal grows is so great that law enforcement can only address a small percentage of them. As the illegal activity increases, weapons and violence accompany it, threatening communities in the area.

Time will tell how all of this plays out, but the growth of illicit marijuana production in the U.S. and the increasing volume of cheap heroin being produced in Mexico and exported across our border are already having a significant impact on communities. With a growing need to move higher-value drugs like heroin, methamphetamine and fentanyl across the border, the cartels that ultimately control illegal cross-border traffic force increasing numbers of desperate migrants to transport these drugs, putting them at greater risk. The number of people being trafficked and forced to work in the U.S. at illicit grow sites has also increased.

As drug consumption continues to increase in the U.S., the cartels will adjust and find new ways to meet this demand, further complicating our ability to address the security of our border and the related humanitarian issues that accompany it.

Guns, ammo, body armor, cash, identification and hundreds of pounds of marijuana are discovered at this illegal grow operation in California. The weapons, including a 100-round drum magazine, are illegal. A previous investigation involving this property owner led to this warrant, resulting in a combined seizure of $178,000 in cash and the arrest of 12 Mexican nationals.

Guns, ammo, body armor, cash, identification and hundreds of pounds of marijuana are discovered at this illegal grow operation in California. The weapons, including a 100-round drum magazine, are illegal. A previous investigation involving this property owner led to this warrant, resulting in a combined seizure of $178,000 in cash and the arrest of 12 Mexican nationals.

Guns, ammo, body armor, cash, identification and hundreds of pounds of marijuana are discovered at this illegal grow operation in California. The weapons, including a 100-round drum magazine, are illegal. A previous investigation involving this property owner led to this warrant, resulting in a combined seizure of $178,000 in cash and the arrest of 12 Mexican nationals.

The Border’s Visual History

My goal with this publication is to bring into these discussions some real-world context as illustrated through photographs. Political leaders and the press tend to focus on the most provocative aspects of the immigration debate and less on why people are leaving, what they are leaving behind and the risks they are willing to take to reach the U.S. You have likely heard or read about the Central American gang MS-13; here, you will see them. You may have heard or read about the dangers of crossing into the U.S. illegally, but here I try to show the impact and risk to the people crossing as well as the challenges law enforcement face both at the border and throughout the U.S.

I also try to bring to this body of work a sense of border life. I do my best in the limited images I have been able to capture to convey the unique and diverse culture of the American Southwest. I have seen the tragic impact of complex border issues on the lives of those living on the border, and I have witnessed the incredible character of people who come together to support one another in difficult times.

Most of the photographs in this book do not need an explanation, but a few will benefit from some context. Where necessary, I have provided a brief explanation of the image. In a few cases, I have referenced the direction in which a photograph was taken. These photographs span a time period and geographies ranging from Mexico in 1995 to El Salvador and the U.S. in 2021.

The debate over our southern border evokes strong opinions and emotions, and I hope the photographs in this book provide both a visual backdrop and a reality check to some of those discussions.

Countries of Origin

People from around the world cross our southern border with Mexico in the hopes of finding opportunity and safety. Their journeys are typically arduous and weeks-long, taking them through dangerous regions controlled by criminal networks. For decades, the majority of people crossing the U.S. southern border were Mexicans in search of work. For most of the past 10 years, individuals from countries other than Mexico outnumbered Mexicans crossing the U.S. southern border, with most coming from the “Northern Triangle” countries of Central America–Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The high rates of violence, corruption, weak justice systems and lack of economic opportunities in countries of origin are the main reasons people choose to migrate. Many migrants are women and children seeking asylum. In 2021, nearly three out of every 10 individuals apprehended at the U.S. southern border traveled from countries in South America. 1

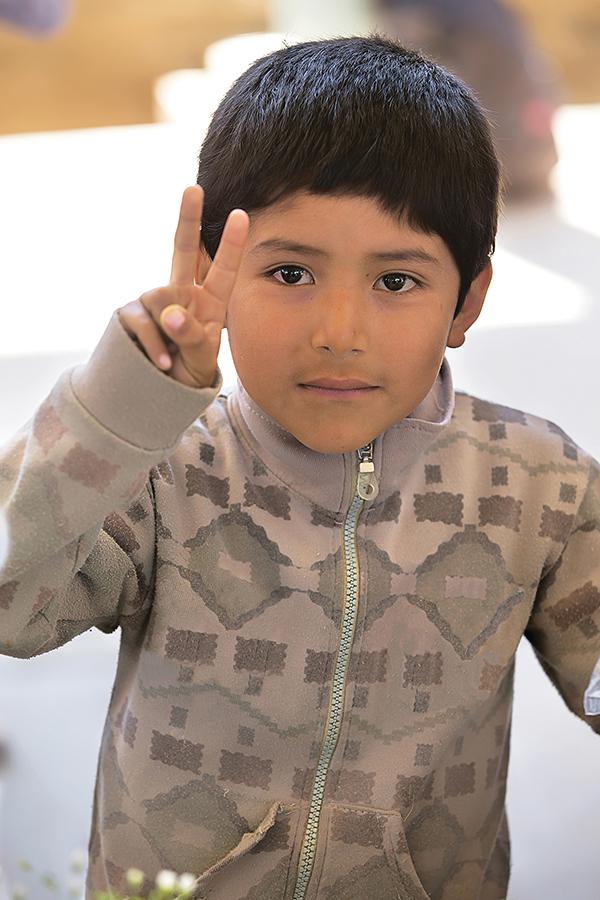

Migration from Guatemala has soared in recent years. Many Guatemalan migrants apprehended at the border are from indigenous communities in the Guatemalan Highlands where agricultural livelihoods have been devastated by ongoing drought. These communities are increasingly targeted by drug cartels and forced to use their lands for illicit drug production.

Over 500,000 young people enter the workforce every year in the Northern Triangle countries of Central America (Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador), but the formal economy only produces 50,000 jobs annually. These economic and demographic pressures create instability within these countries and influence migration patterns to the United States.

In 2005, I traveled to a garbage dump outside of Tegucigalpa, Honduras. There were a number of young children living at the landfill. We were told by several of the girls, who ranged in age from 12 to 15, that they would sell their bodies to the truck drivers in order to have money for food. They would also sniff glue to numb their hunger pains.

These two women walk through the El Centro neighborhood in San Salvador, an area well known for prostitution. These areas are also breeding grounds for sex trafficking.

Death Train

The Death Train, or “El Tren de la Muerte,” refers to freight trains used by migrants to travel north from southern Mexico to cities along the U.S./Mexico border. Migrants have long used this dangerous form of transportation on their journey to the U.S. It gained its nickname because of the many migrants who have fallen off and died or sustained life-altering injuries.

The Death Train, or El tren de la muerte, refers to the network of freight trains that travel north from southern Mexico to cities along the U.S./Mexico border. Migrants have long used this dangerous form of transportation on their journey to the U.S.

As a train departs Veracruz, Mexico, a young man realizes it is traveling south. He begins jumping between cars in search of a ladder so that he can get off and catch a northbound train.

In Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, I talked to a young man who fell from the Death Train; he was recovering at the Albergue Jesús El Buen Pastor migrant shelter. Even after having his lower right leg severed by the wheels of a train car, he insisted he was going to continue his journey to the U.S.

Enforcement South of Border

Under pressure from the U.S. government, the Mexican government has increased immigration enforcement on their southern border with Guatemala and in the country’s interior.

A group of Mexican military personnel sit just south of a vehicle barrier located along the border east of Douglas, Arizona.

The Mexican National Guard patrols along the south side of the U.S./Mexico border fence, confiscating ladders used to breach the fence on the Mexican side.

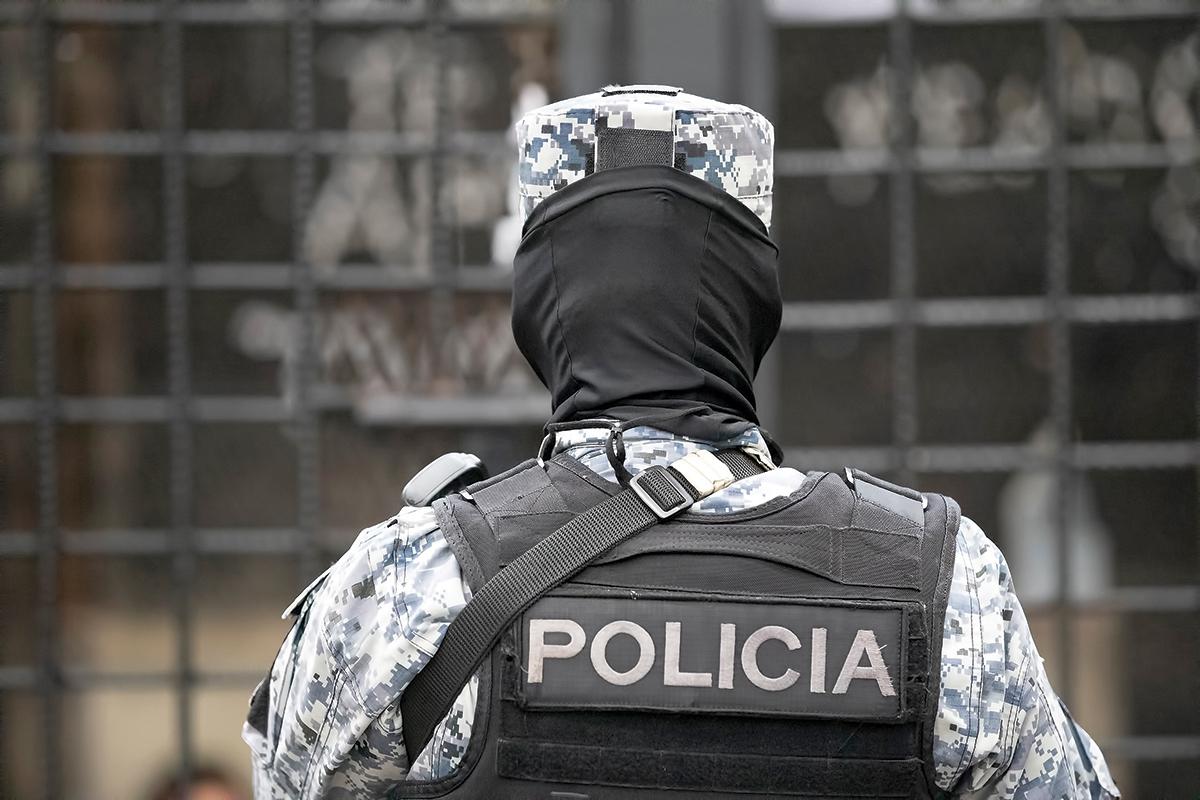

In many countries where cartels or gangs operate, police officers must disguise their identity in order to avoid retaliation by organized criminal groups.

In El Salvador, gangs operate with impunity by controlling large areas of the country. MS-13 and 18th Street are the predominant rival gangs, though there are also many gang “cliques” or sub-groups as well. Their presence is a constant threat to the lives and livelihoods of all Salvadorans.

The Colombian military searches for illicit coca fields. The countryside is littered with many small fields that are often located on steep hills in thick forest. Finding the fields is the first step; however, reaching them to destroy the coca can be extremely difficult.

K-9s trained to identify land mines are used to avoid injuries while operating in the illicit coca grow areas of Colombia’s countryside.

At the border of Mexico and Guatemala, these two women have crossed the Suchiate River from Guatemala. This officer is requesting identification and is likely asking the purpose of their trip.

Preparing to Cross

The U.S. border with Mexico spans nearly 2,000 miles, and over the long history of migration across it, migrants have established common routes to reach the U.S. Those traditional routes are shifting with increased border enforcement and changing immigration policies. At the same time, many migrants have taken advantage of more tolerant immigration policies and simply walk across open areas to give themselves up to Border Patrol. Depending on Border Patrol’s Areas of Responsibility (AOR), the migrant's country of origin, Border Patrol resources, and the Mexican cartel’s business strategy for managing the flow of migrants and drugs, where and how migrants cross is constantly changing.

In Altar, Mexico, a group of people wait to be escorted to the border. The young man to the left was traveling by himself; he told us he was 15 years old and heading “north” to join his family in the U.S. (2004)

During the mid-2000s, the number of people crossing the U.S. border from Mexico increased dramatically. This local Catholic priest in Altar, Mexico, held multiple masses each day for those preparing to make the dangerous trip across the border and through the desert.

This truck is transporting people on the final stage of their journey to cross the border into the U.S.

Crossing

The U.S./Mexico border is the most frequently-crossed international land border in the world.2 Unaccompanied minors, families, workers, smugglers, human traffickers and drug mules make up the millions of people who cross into the U.S. every year, both legally through official ports of entry (POE) and illegally. To facilitate the illegal crossings, particularly of those smuggling narcotics, scouts on the Mexican side of the border constantly surveil and report on U.S. border enforcement activities.

Scouts ride just south of the U.S. border to determine the best areas to cross. They often disguise themselves as ranchers, road workers or sometimes just kids having a party. If they are along the border, chances are they are reporting conditions and activity to the cartel that controls that area of the border.

A smuggler returns across the Rio Grande River to Mexico after making multiple trips with migrants, seen in foreground.

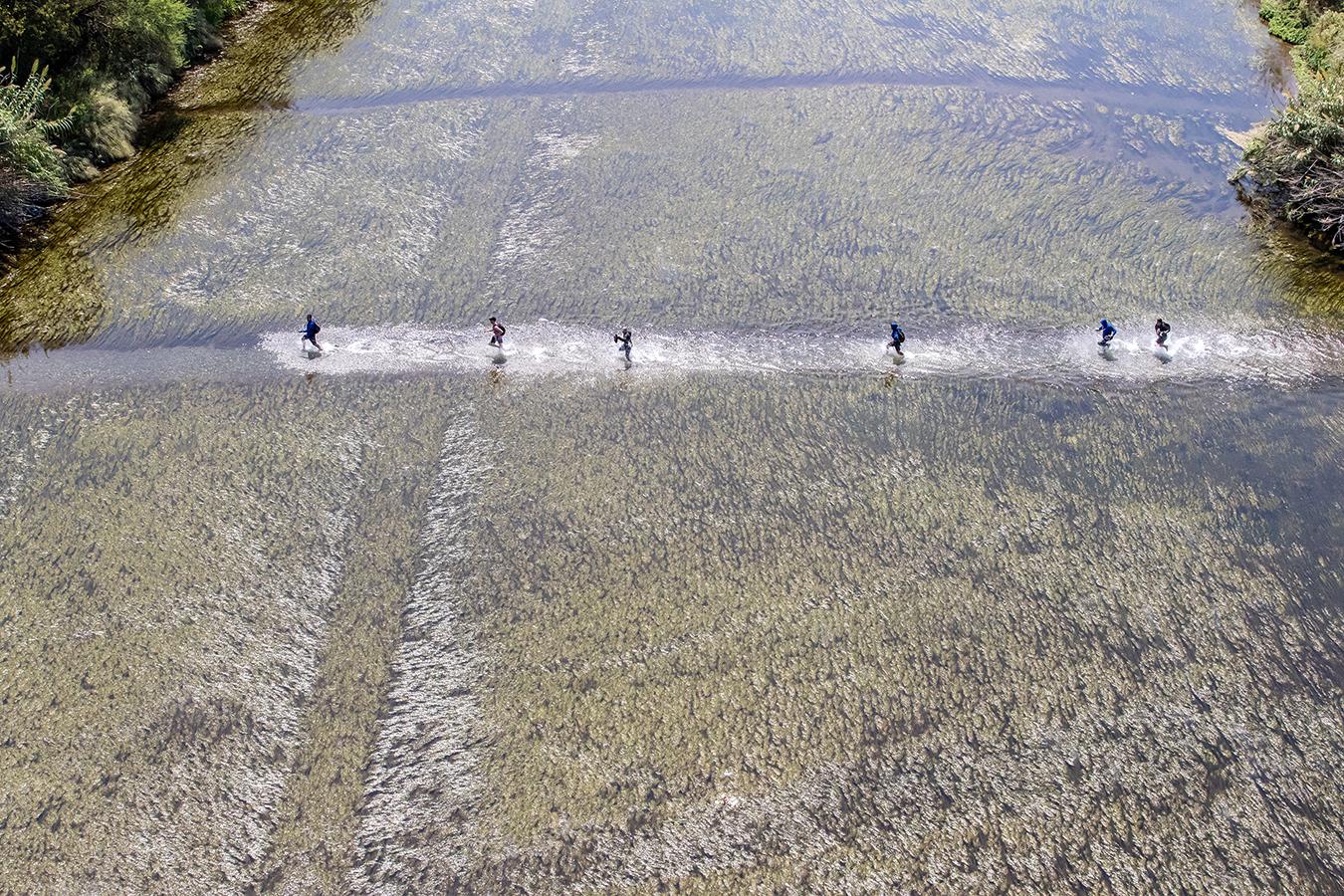

This group of people is crossing the Suchiate River from Guatemala to Mexico. Some are crossing as part of the everyday commerce; others are crossing with the intent of traveling north to the United States.

A smuggler assists a migrant across the Rio Grande River.

A scout lays along the banks of the Rio Grande River on the U.S. side. His job is to report Border Patrol movements to his colleagues in Mexico. His cell phone is enclosed in a plastic bag to keep it dry.

A smuggler returns to Mexico after delivering a group of migrants to the U.S. side of the river.

Faustino Landa Badillo, 69, sits on a pile of rocks waiting for Border Patrol to arrive. He shows me his identification card issued by the Texas Department of Public Safety, which expired in 2002. He explains that he rode “La Bestia” (the “Death Train”) for part of his journey.

Migrants increasingly use camouflage clothing to disguise themselves on their journey north.

I waited on the tracks in Veracruz, Mexico, at midnight to get a glimpse of the Death Train. The train passed just minutes after this photo was taken, and the force of the train almost knocked me off my feet. I could see the arms and legs of riders dangling as it sped past me.

U.S.-bound migrants cross the Usumacinta River from Guatemala into Mexico. They will follow the tracks north until they can hop on a train.

Only a few miles north of the U.S./Mexico border, these migrants move quickly to their pickup location.

Photographing through a hole in the fence east of Naco, Arizona, I can see a scout moving his ladder to another area. This fence was constructed out of old Vietnam helicopter landing mats; in 2016, this area of fencing was replaced by 20-foot bollard fencing with an anti-climb plate on top.

Signs of Crossing

Our border regions have always been shaped and molded by migration, including by the objects migrants and border residents leave along the border to either help or deter crossings. Some of the physical signs of crossing point to how dangerous, and even deadly, the trip across the border can be.

It was not uncommon in the mid-2000s to find clothing hanging from trees near the border, marking the path of migrants and, according to more disturbing accounts, signifying where coyotes had raped women they were bringing across the border.

Along the border in the Yuma area, abandoned women’s clothing marks the path of migrants. Former Border Patrol agent turned civil rights attorney Brendan Lenihan described such displays of clothing draped on trees–and in this case, a steel fence separating the U.S. from Mexico–in an article for the American Spectator as follows: “The Border Patrol calls these “rape trees.” It’s difficult to know whether these displays are merely symbolic of a woman’s vulnerability in this place or are the actual trophies of sexual violence. Either way, women who understand the risks of this desert sometimes ingest morning-after pills before even attempting to cross.”

Emergency water stations can be found in various locations in the desert, often where the highest number of migrant bodies are recovered.

A small sample of abandoned camouflage clothing that was recovered on a border ranch in Arizona.

In some areas, people leave water for crossers traveling through the desert. This water was placed in several areas of the Tohono Oʼodham Indian Reservation in Arizona.

The bodies of over 7,100 migrants have been recovered from the mostly inhospitable desert areas north of the U.S. border since 1998. Some can be readily identified through documents and other possessions found with their body, while others remain unidentified. It is likely that many bodies are never found.

On one of our ranches in Arizona, a shoe is buried in the ground as a directional marker for the trail. There are many different signs that are found across the ranch; they are designed to help drug mules stay on the correct course.

Our ranch in Arizona experiences frequent crossings; here, you can make out hand prints on the fence bordering our ranch where people have climbed over.

When we purchased our farm in Texas along the Rio Grande River, abandoned life vests (painted black) and old inner tubes were found in a shed on the property. In the past, they had been used to wade across the river to reach the U.S.

Stash houses are common along the border; they are typically abandoned or condemned houses. Smugglers moving large amounts of people or drugs will sometimes rent houses. Many of the houses are full of trash, water bottles, food wrappings, clothing and human waste.

The Impact of the Desert

In the late 1990s, immigration and border enforcement practices pushed migrants to attempt to cross in more remote and dangerous places, which resulted in record deaths. Below are images reflecting these dangers. Note: these images may not be appropriate for individuals who are sensitive to photographs depicting death. To view the image, click on the eye icon.

A Border Patrol agent discovers a male migrant who died in the desert, only a few miles north of Mexico.

A special unit of Border Patrol locates a group of migrants that are lost, hungry and injured. These agents are trained to provide medical care and assistance.

While flying a search and rescue mission we locate a group of migrants in distress. The female is severely dehydrated. She was taken by helicopter to Yuma Regional Medical Center and was released following three days of medical care.

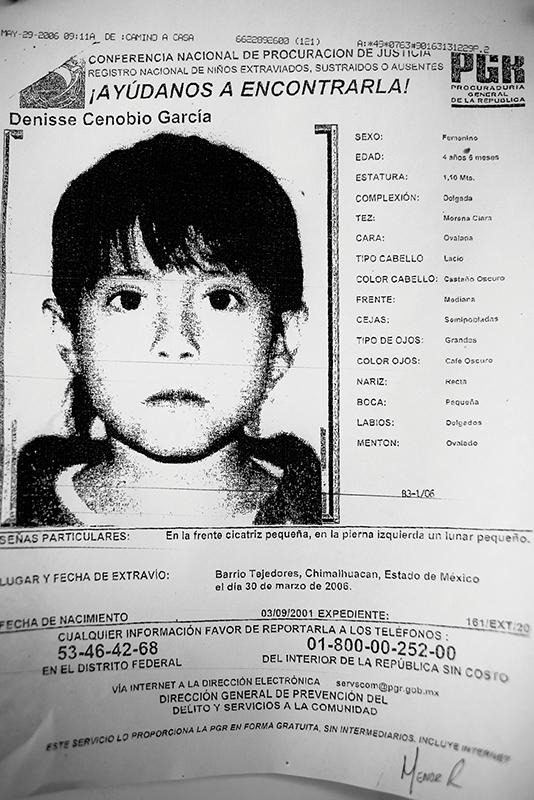

The violence in Mexico has resulted in tens of thousands of missing persons and the confirmed deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. Illegal immigration, and the smuggling networks that facilitate it, has also left thousands of families without knowledge of their family memberʼs whereabouts. This four year-old child went missing in 2006.

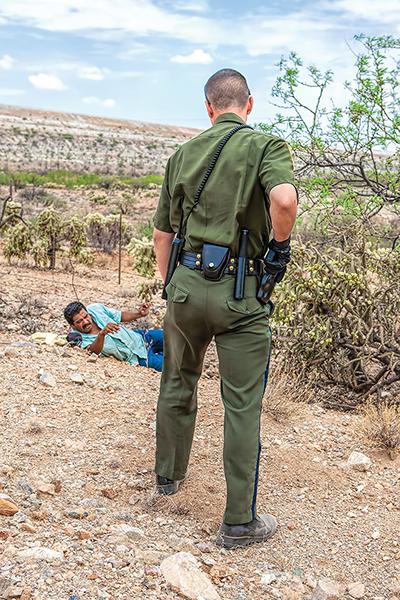

When this man was found by Border Patrol, he was dehydrated and his feet were severely blistered. He described to the agents that he had left behind several people traveling with him, whom he feared were no longer alive.

At one point in time, the Pima County Medical Examinerʼs Office in Arizona had to lease and operate a refrigerated trailer to manage the number of bodies that were recovered from the desert.

Apprehensions

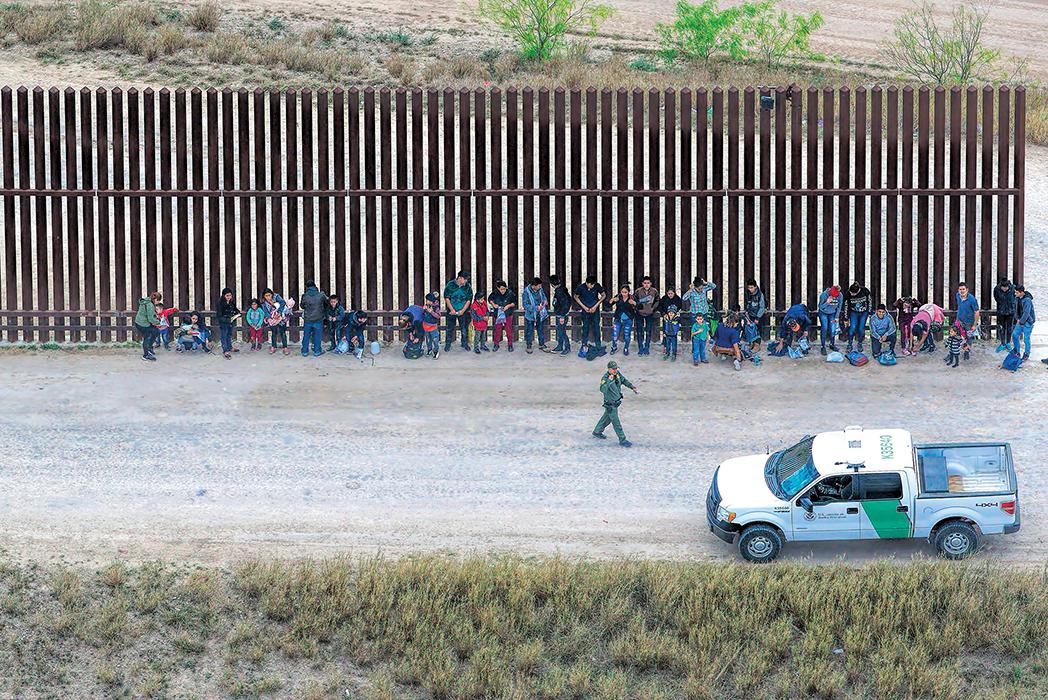

During Fiscal Year 2021, apprehensions at our southern border hit a record high of nearly 1.7 million enforcement encounters.3

3https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-land-border-encounters

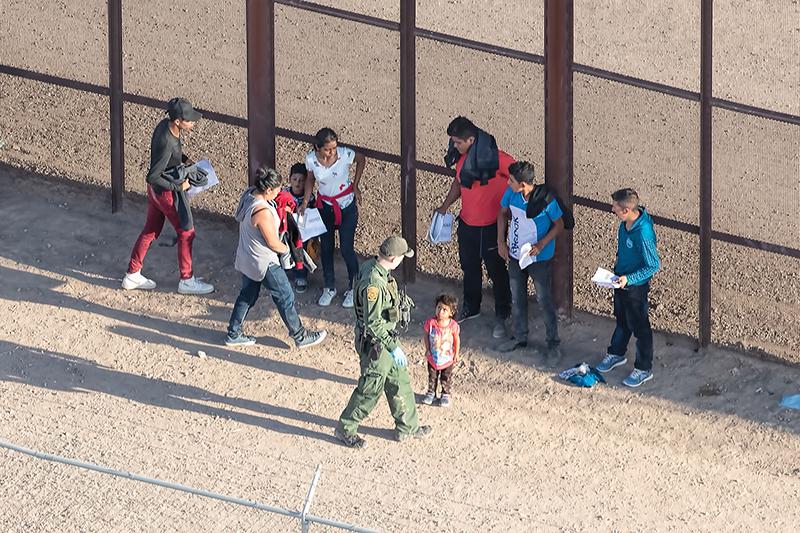

In recent years, many apprehensions are now unaccompanied minors and family units that often include small children.

Many migrants willingly turn themselves in to Border Patrol agents in the hopes of seeking and being granted asylum.

To avoid apprehension from Border Patrol, this woman walks back into Mexico along the Morelos Dam on the Colorado River outside of Yuma, Arizona.

Unlike asylum seekers who actively seek out Border Patrol agents to turn themselves in, these men in camouflage were trying to evade detection. Prior to apprehension, these men dropped the drug bundles they were smuggling, which Border Patrol later located.

The port of entry (POE) in Antelope Wells, New Mexico, shown above and below, was one of the main arrival points for families traveling from Central America and Mexico in 2019. Historically, this POE had received the least amount of traffic of any U.S./Mexico POE. However, this photo is indicative of a phenomenon that the U.S. and Border Patrol have experienced in recent years: enforcement in other areas is driving individuals and families to arrive in large numbers here and turn themselves in to authorities.

In recent years, large groups of migrants have overwhelmed Border Patrol facilities. Temporary shelters like these became more common as group sizes increased.

In the early 2000s, apprehensions of undocumented migrants exceeded 1.6 million in a single year. This shelter was constructed close to the border as a temporary facility to hold individuals who had illegally crossed into the U.S. These individuals were later transported to a primary Border Patrol facility to be processed.

Individuals apprehended in the field are transported to a Border Patrol facility to be processed. An effort is made to keep unaccompanied juveniles separated from adults.

This migrant’s biometric data is collected during processing.

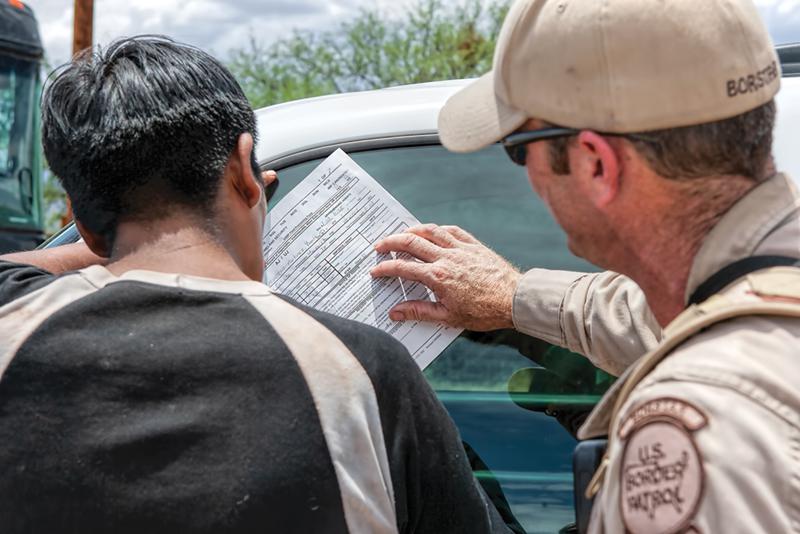

After being apprehended, migrants are processed and their information is collected and logged.

A 21-year-old mother being detained at a U.S. Border Patrol facility describes to an agent how she sent her three-year-old son across the border checkpoint with a “coyote.” With no way to contact the smuggler, she doesn’t know if she’ll ever see her son again.

This young girl does not understand why her mother is wearing an ankle monitor. The practice of using ankle monitors became more common as Border Patrol was overwhelmed by the volume of migrants. This process was commonly referred to as “catch and release,” a result of a lack of holding facilities. Once processed, migrants were released into the interior of the country with a “notice to appear” for an immigration hearing at a later date.

Smugglers

Based on drug seizure data, illegal drugs are more likely to be smuggled through official POEs than trafficked between POEs.4 Seizures of illicit drugs, both at POEs and between POEs, have increased in the past five years. Smugglers use a variety of methods to traffic drugs into the U.S. including on foot, as you’ll see in the below pictures, as well as by air, sea, and even through underground tunnels.

The following images were captured by trail cameras on our Arizona ranch property and Texas farm property.

Similar to the way drugs flow north from Mexico to the U.S., where they then devastate entire families and communities, weapons and cash are smuggled south from the U.S. into Mexico, where they are used by the cartels to terrorize Mexican citizens.

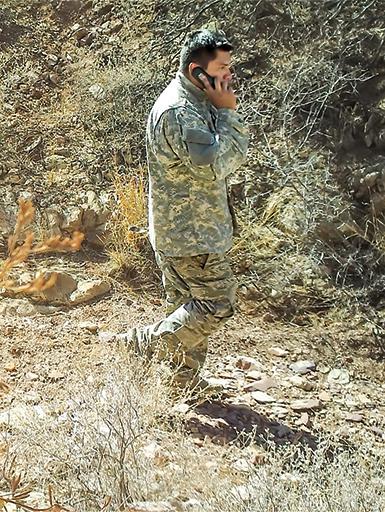

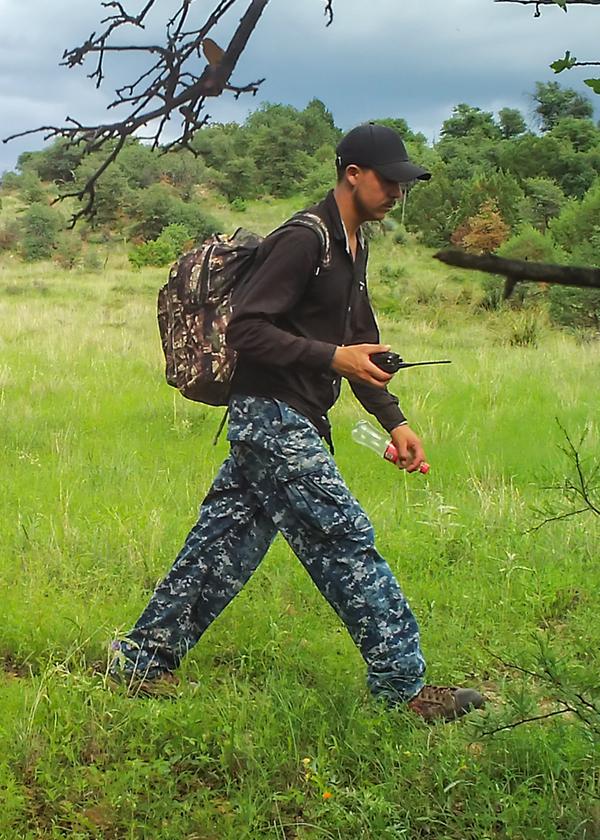

Smugglers are in constant communication with scouts to determine how to avoid Border Patrol and other law enforcement. They use cellphones and two-way radios.

Smugglers often wear booties or wrap their shoes with cloth or burlap to disguise their tracks. The materials used for the booties make specific shoe prints indistinguishable, making individual identification impossible.

Scouts, mules and coyotes return south to Mexico to replenish supplies, to prepare to transport their next load of drugs or to guide the next group of people across the border. The fence these scouts are climbing is the southern cattle fence on our ranch; in the background, you can see the vehicle barrier separating the U.S. and Mexico.

On several occasions, our cameras captured this same individual moving south. He has different weapons in different photos. These images were captured during the same time period that a federal agency issued a bulletin warning that a specific cartel was sending members of its organization into Arizona to conduct surveillance and target confidential informants who had assisted U.S. law enforcement.

After Border Patrol apprehended a group of drug mules, this group of armed individuals on several 4-wheelers and a utility vehicle entered our ranch to recover drugs which the mules had hidden prior to their apprehension. Cartels have been known to use GPS locators to recover high-value drugs; they have also been known to hide high-value drugs such as meth, heroin and cocaine in marijuana packs.

The individual in the foreground is carrying a water jug that has been painted black to minimize reflections off the plastic to reduce the likelihood of being spotted by Border Patrol.

Cartel scouts head back south in an attempt to avoid Border Patrol.

Narcotics being smuggled across the Rio Grande River into Texas.

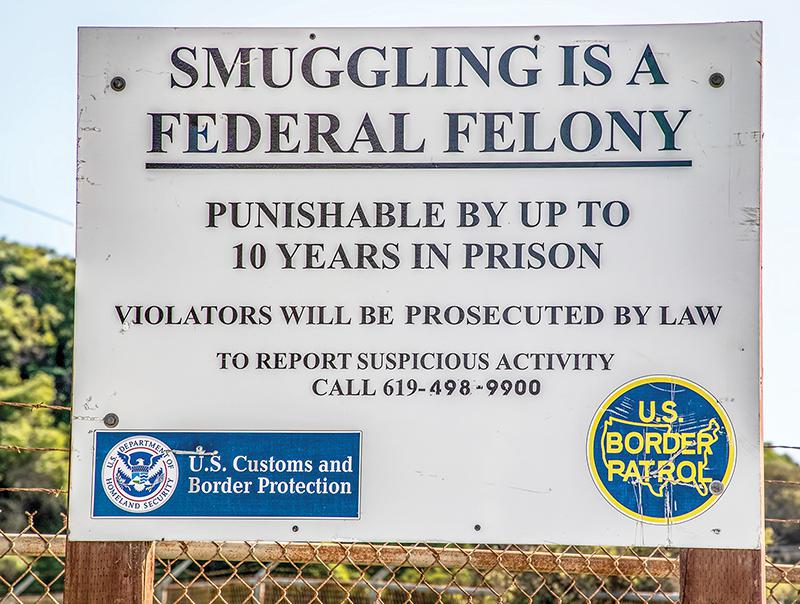

Signs

Official signs near the border acknowledge the near-constant smuggling activity in these regions. While some signs warn of the consequences for engaging in cross-border smuggling, others alert travelers of the dangers of traveling through known smuggling routes.

Federal regulation allows Border Patrol to operate and conduct searches and seizures within 100 miles of any international boundary. This is one of 170 internal Border Patrol road checkpoints located within the U.S.

Ports of Entry and Checkpoints

U.S. Customs and Border Protection routinely confiscate thousands of pounds of marijuana, cocaine, heroin, meth and fentanyl at our legal land crossings with Mexico. Border Patrol also has the authority to establish checkpoints within 100 miles of any land or marine border to conduct routine searches. These searches also result in considerable amounts of drug seizures.

In 2018, interior checkpoints seized enough fentanyl, cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine to kill the equivalent of 390 million people from overdoses.

Border Patrol agents use K-9s to help detect drugs, which are often located in hidden compartments inside of vehicles and trucks. Drugs are also found in tires, engines, toys and even food products.

Surveillance

It is difficult to comprehend the vast amount of geography and varying topography that Border Patrol is required to secure. They rely on a multitude of different assets to help them with that task, including patrol vehicles, watercrafts, horses, K-9s and helicopters, as well as surveillance towers, cameras, motion sensors, drones, radar and aerostats.

Border Patrol uses tire drags to remove tracks from the road; they will later return to the area and check for fresh footprints, indicating a new crossing.

Surveillance towers help Border Patrol detect and track movement on the border. In addition to cameras, Border Patrol uses sensors that are triggered by movement to detect where there is cross-border activity.

It is difficult to comprehend the vast amount of geography and varying topography that Border Patrol is required to secure.

Aerostats can be an effective tool for air surveillance. They often operate as high as 10,000 feet, and some have a radar system that can detect aircraft at a range of 200 miles. They can also be used to detect low flying aircraft that are entering the U.S. illegally.

A drone returns to Fort Huachuca Army Base in Arizona after completing a surveillance mission.

Agents, with the support of the National Guard, monitor border cameras.

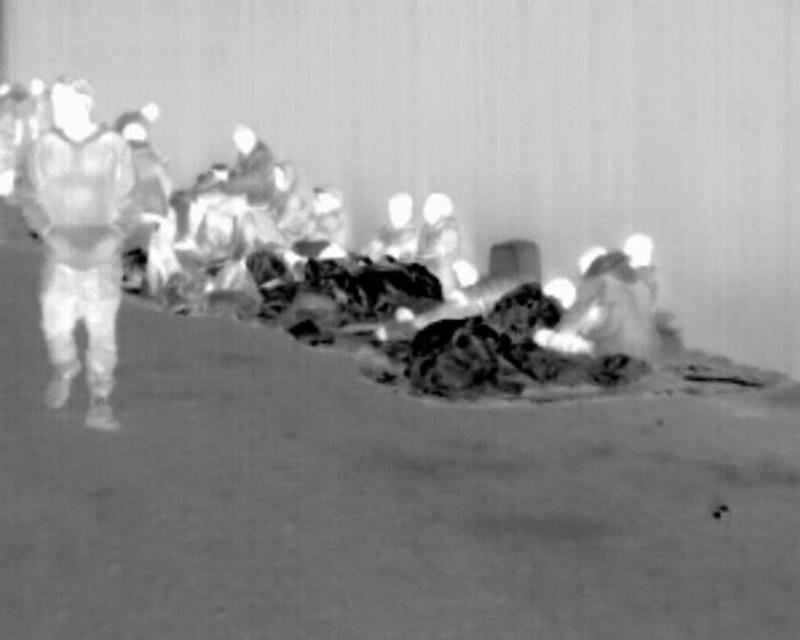

With the right equipment, movement at night can be detected as easily as during the day.

Border Enforcement

Customs and Border Protection is the largest federal law enforcement agency in the U.S. with more than 63,000 employees. Approximately 18,500 border agents are stationed along our southern border.5 Their enforcement activities include patrolling the border, surveillance and apprehending migrants or smugglers. Their duties also often include rescuing migrants from dangerous situations or recovering bodies.

The Rio Grande makes up nearly half of our country’s southern border with Mexico. In many places, the river serves as a natural barrier; however, migrants and smugglers often find ways to cross. Border Patrol has a number of surveillance watercrafts on the river at any given time.

Air surveillance and ground personnel work together to identify, locate and apprehend drug smugglers in remote areas.

Border Patrol agents have to traverse rugged and dangerous terrain along the border.

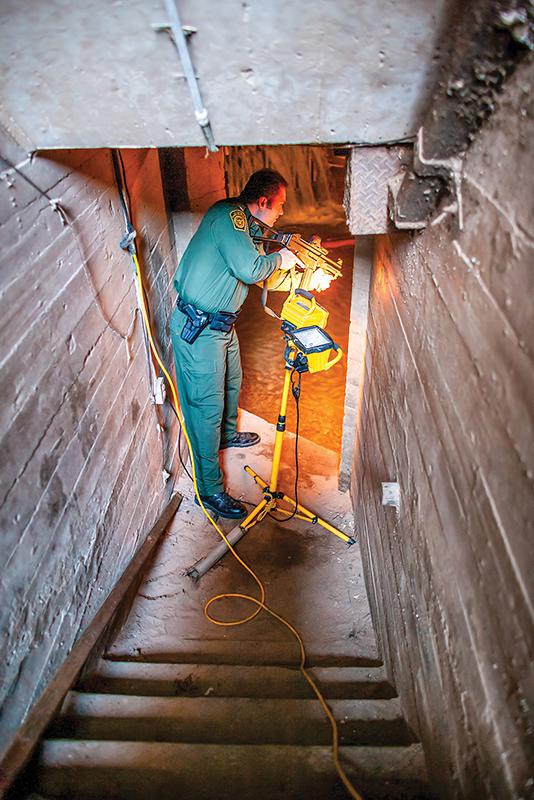

A Border Patrol agent checks an underground drainage tunnel running between Nogales, Sonora, and Nogales, Arizona. The tunnel has been used to smuggle people and drugs and can be deadly during flash floods.

National Guard troops are permanently stationed at a number of locations along the border.

Fence Construction

There is approximately 771 miles of physical, man-made barriers along our nearly 2,000-mile border with Mexico.6 Much of these barriers are in high-traffic locations and include structures that are intended to block vehicle access and foot traffic. During the Trump administration, construction of barriers was started in remote areas of the border where natural geographic features already made crossing extremely difficult. Some fencing, drainage, lighting, camera systems and seismic cables were not completed with the change in administration.

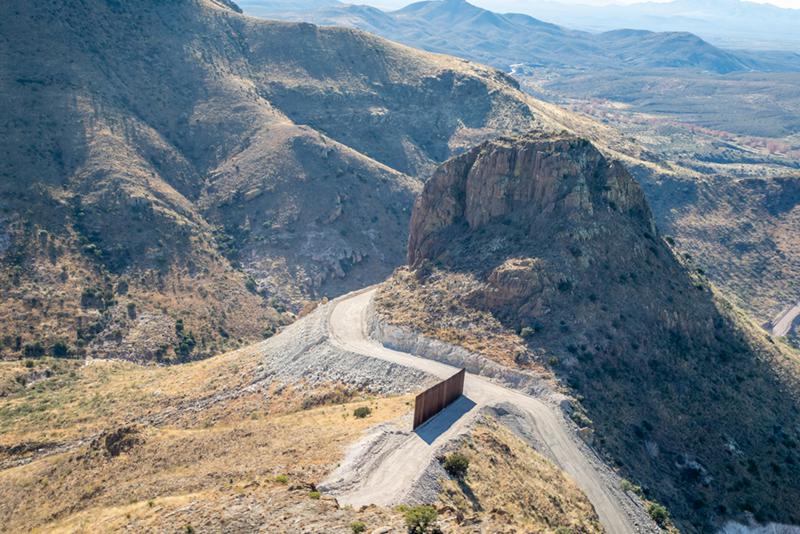

New fence construction in the Huachuca Mountains required blasting in national forests. It is estimated that once inaccessible areas like this cost as much as $70 million per mile to construct roads and fencing.

Vehicle barriers have been replaced with primary pedestrian barriers in many locations along the border.

Some of the areas where fencing projects were started were in remote areas with minimal previous crossings recorded. New roads will make them more accessible to foot traffic.

East of Yuma, Arizona, special equipment is used to create a “pre-footing” for new fencing. The sand is too soft to dig a footing because the sides constantly cave in, so a concrete pre-mix is poured into the first trench. After the mix has set, the trench for the fence is dug into the mix, and the final fencing and concrete footing is completed.

A group of smugglers moves away from the fence in Mexico as law enforcement officers approach. One man is carrying a band saw and another has a chisel hammer to cut through concrete. The latter is not shy about expressing his opinion.

This fence has been cut and repaired. Fences are often cut with chop saws or other tools so vehicles and people can cross the border.

Constructing a fence creates an unnatural barrier. It is usually assumed that it only restricts people, vehicles and wildlife, but it also restricts water flow. In this case, the water washed out the existing fence, and it was replaced with gates (seen below) that are designed to be open during monsoon season.

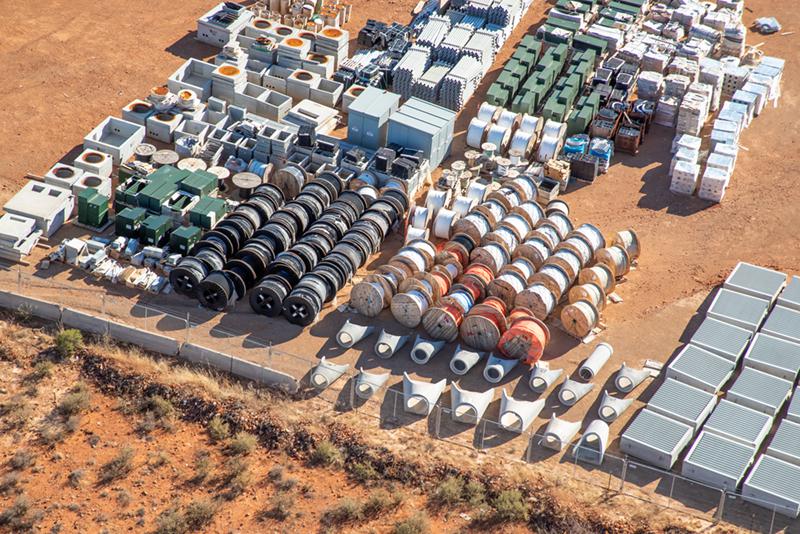

When border fence construction was stopped in January 2021, millions of dollars of mobilized materials were left behind from California to Texas.

The following six photographs show incomplete border fence construction after construction was abruptly stopped as a result of a change in presidential administrations in the U.S.

Unfinished drainage, missing road pack, incomplete lighting, partially buried seismic cables, missing gates and half-built bridges create hazards, making Border Patrol’s job more difficult, as well as having a negative impact on ranches along the border.

The Border

The border region has some of the most beautiful landscape in the U.S. Some landscapes have been permanently altered by the construction of border barriers, and in others, nature has provided its own formidable natural barriers at the U.S./Mexico border.

The person on the right, behind the fence in Mexico, is looking through binoculars. He is a scout passing along information about the movements of law enforcement.

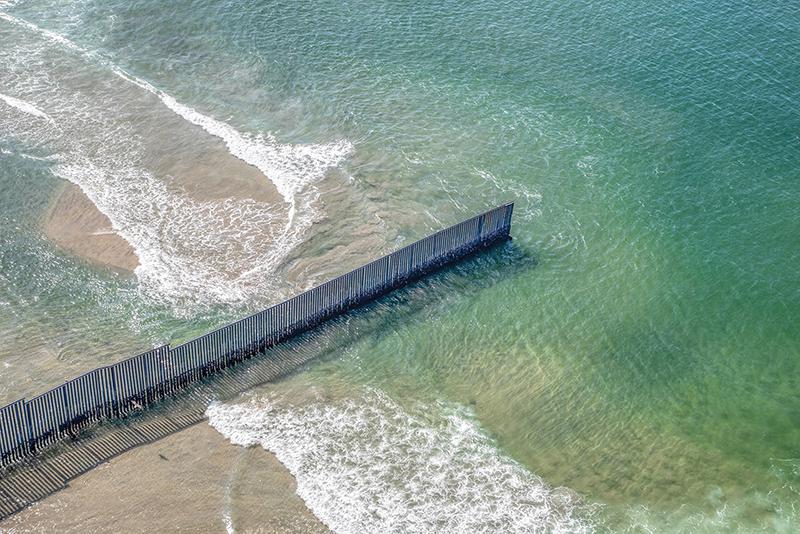

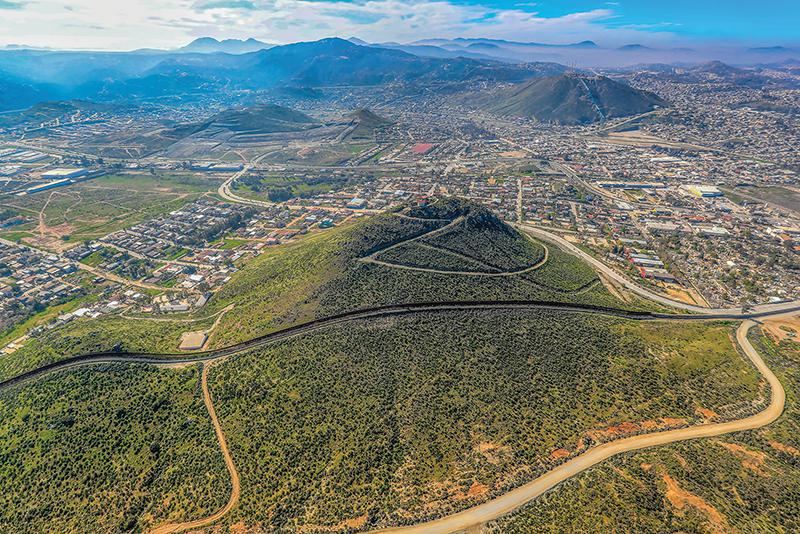

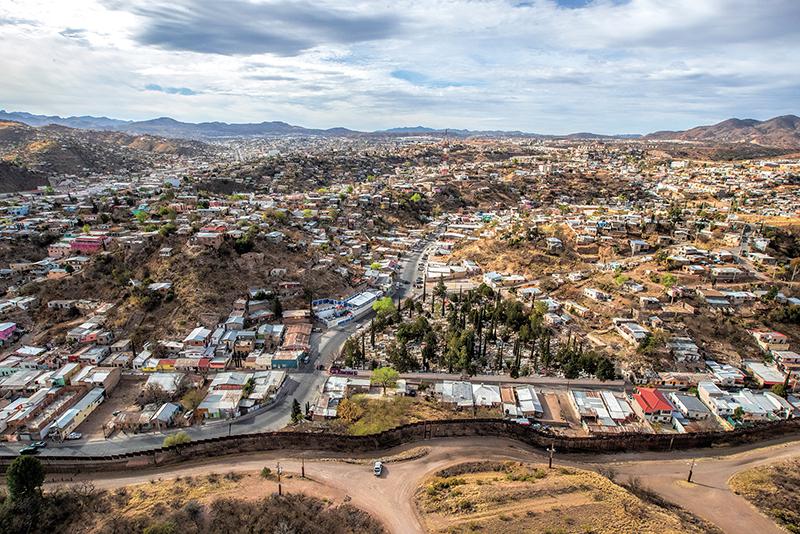

The fence separating San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Mexico, begins in the Pacific Ocean and runs 14 miles east, ending at the base of Otay Mountain.

In many places along the U.S./Mexico border, the only demarcation is a simple border marker, most of which date back to the 19th century.

There are vast expanses of uninhabited land along the border, making illegal crossings dangerous.

Border fencing can begin and end abruptly, often because of natural barriers. Typically, rock outcroppings or mountains are not practical or cost effective to build across.

Agricultural production in Mexico occurs right along the border fence.

Shifting sand dunes make up part of the U.S./Mexico border in California, which have presented particular challenges for Border Patrol and security infrastructure.

A track hoe cleans out sand that has blown up against part of the fence located in the Algodones Dunes, which runs 45 miles along the U.S./Mexico border in California.

From the air, this photo shows Arizona on the left, Mexico on the far side (top) of the fence and California on the near side (bottom) of the fence.

This photo is from a boat at the same location on the Colorado River looking west; the American flag is at the POE a few miles away.

This fencing was replaced in 2016. It appears that during construction some of the fencing being replaced was stolen and put up on the south side of the border in Mexico. One can only speculate, but it is likely now used for climbing practice.

An unfinished section of fence stands in Guadalupe Canyon. This construction will leave permanent scars in some of the most remote and beautiful areas of the Southwest.

Big Bend National Park features stunning canyons that drop down to the Rio Grande and extend for over 100 miles along the border.

This photo of farmland in the U.S. (shown on left) illustrates why a border barrier cannot be built on the actual border because the river itself is the border. In addition, periodic flooding prevents a barrier from being built on the riverʼs edge. Below the narrow strip of vegetation running down the left side of the farmland (about half way up) is a natural flood zone; the proposed barrier on this farm is designed to be built all the way back where the farmland ends, almost three-quarters of a mile from the river.

Large portions of farmland in Texas lie on the south side of the border barrier. In some places, cemeteries, homes, wildlife preserves, a golf course and thousands of acres of private land are “separated” from the rest of Texas by a border barrier.

On the Rio Grande River, Border Patrol occasionally discovers tunnels dug through the bank of the river. This tunnel had been heavily concealed by brush and connects into the sewer system that runs through McAllen, Texas.

Depending on how the river is measured, the Rio Grande is considered either the fourth or fifth longest river in the U.S.; it starts in Colorado and ends in the Gulf of Mexico (shown here) and is the actual U.S. border with Mexico for the state of Texas.

Life on the Border

For those who live and work on both sides of our southern border, the political debates around border security, immigration and the violence and crime created by drug cartels impact their day-to-day lives in ways that few people can imagine.

Topography in the Southwest spans from hot desert climates to rugged mountains. Rescue crews are regularly called to assist with injured or lost hikers, and ranchers or law enforcement who have been hurt in remote and difficult terrain.

Ranchers can easily have their livelihoods affected from wildfires that damage important grazing areas.

Fencing along the border creates a barrier for people and wildlife, as well as natural events. Heavy rain can plug fence gates with debris, changing the flow of water and forcing powerful streams of concentrated flow, creating flooding and causing damage to property or the fence itself.

West of Douglas, Arizona, cattle are moved from Mexico through the border fence to the United States.

Our countryʼs border is also home to vibrant and productive industries that account for a quarter of our countryʼs GDP.

Many industries in the U.S., particularly the agricultural sector, depend on migrant labor. Current guest worker visa programs fall short of the demand; as a result, many workers cross unlawfully and are employed illegally.

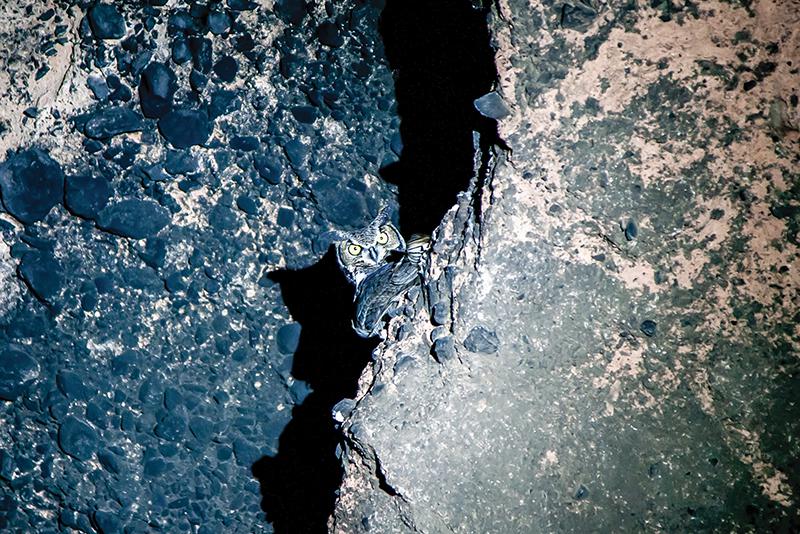

Southeastern Arizona has a number of predators, including coyotes, Mexican gray wolves, foxes, black bears, mountain lions, bobcats, ocelots and occasionally, a rare jaguar. The jaguar was last recorded in southern Arizona in 1938 until one was killed in 1987 in the Dos Cabezas Mountains, close to where this photo of a mountain lion was taken.

The southeastern corner of Arizona plays an important role in the migration of nearly 35,000 sandhill cranes. The climate, topography and fall harvest in this area provides an ideal environment for the craneʼs wintering grounds. Researchers who track banded cranes have documented that some cranes who spend the winter months in Arizona travel as far as Siberia to nest.

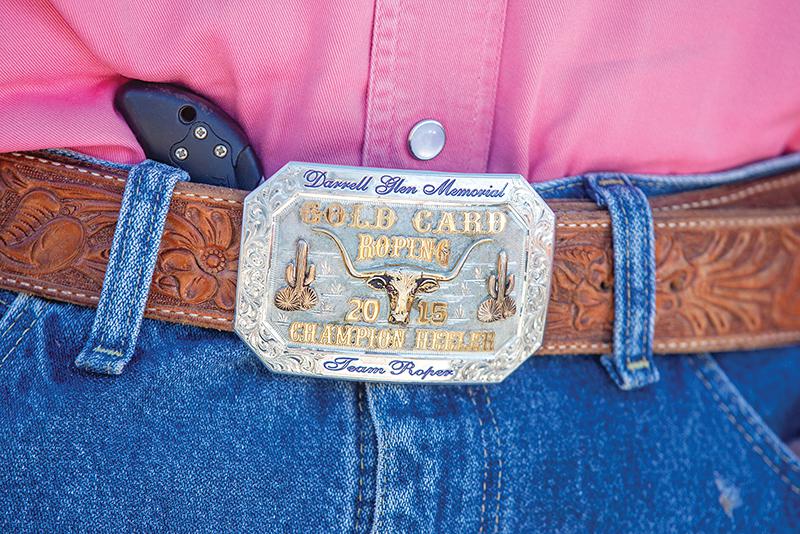

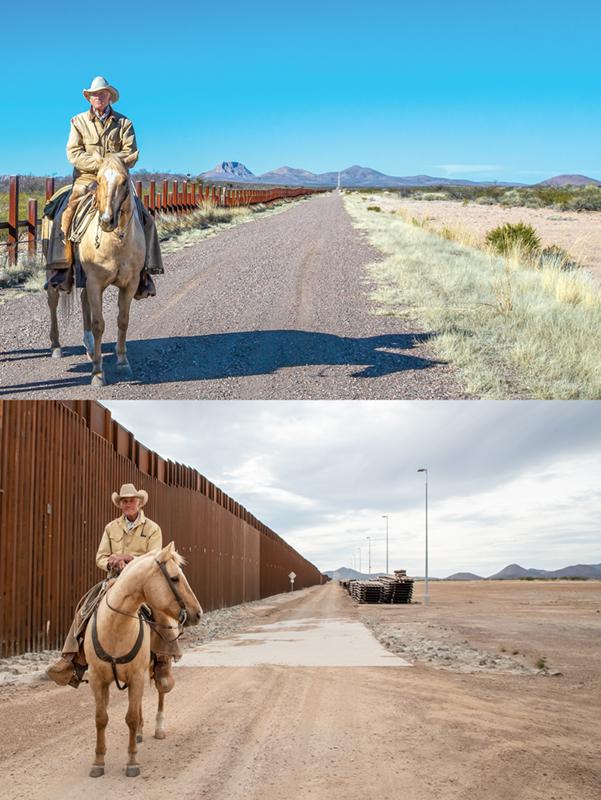

Rancher Warner Glenn is pictured on the border just east of Douglas, Arizona, in 2017 (TOP). Four years later (BOTTOM), he is in almost the same location, showing the impact of the new border fencing on the landscape. What is not as apparent is the effect on wildlife and water flows.

About The Photographer

Howard G. Buffett first got involved with U.S./Mexico border issues in 1990 while serving as a member of the Douglas County Board of Commissioners and working with the United States Trade Representative. He was asked to serve on a commission to review the impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on local communities in the U.S. Later, Howard traveled and worked extensively in a business capacity in Mexico and the Northern Triangle countries of Central America, first as a Senior Executive at Archer Daniels Midland and later as Chairman of the GSI Group.

Since its founding in 1999, the Howard G. Buffett Foundation has worked in many countries in Latin America that are impacted by cross-border migration into the U.S. and affected by U.S. immigration and border control policies. The Foundation has committed over $700 million to address forced migration and its drivers in the U.S. and Latin America. Howard has interviewed gang members in Salvadoran prisons; visited hundreds of rural farmers throughout Latin America; met with countless policy makers working on border and immigration issues in the U.S. and abroad; and traveled extensively within countries of origin to research the factors driving migration.

Howard’s experiences overseeing ranches and farms on the U.S./Mexico border; serving as a sworn law enforcement officer; traveling and photographing the U.S. southern border several times over; and countless hours spent working with Border Patrol, local law enforcement agencies and border ranchers have all contributed to his unique perspective on how to address the twin challenges of securing our border while dealing with the humanitarian crisis of forced migration.

Howard has received prestigious awards from a number of foreign governments, including several in Latin America: the Aztec Eagle Award in 2000 from the President of Mexico, the highest honor bestowed on a foreign citizen by the Government of Mexico; the Fe en la Causa Medal in 2017 from the government of Colombia, the highest honor bestowed upon a civilian by the Colombian Military; the Order of San Carlos in 2019 from Colombian President Iván Duque Márquez, which honors individuals who have made outstanding contributions to the nation of Colombia, especially in the field of international relations; and the Order of Police Merit Gold Cross in 2019, the highest honor awarded by the President of El Salvador for acts of service supporting the National Civil Police.

Howard has traveled to over 150 countries and authored two New York Times’ bestselling books including Our 50-State Border Crisis: How the Mexican Border Fuels the Drug Epidemic Across America. Howard is also the executive producer of The River and The Wall, a documentary focused on the impact of a physical border wall on the Texas-Mexico border region. For over 30 years, Howard has used his photographs to document, educate and inspire action.

Howard in 2006, photographing and talking to a migrant detained by Border Patrol. Border Patrol policies then allowed for more interaction with detained individuals.

Howard has spent almost 20 years visiting the border with Border Patrol agents and other organizations to understand its challenges. (2008)

Howard tours a section of the U.S./Mexico border east of Douglas, Arizona with rancher Warner Glenn. (2017)

Photo credit: Eric Crowley

This family has just crossed under the fence in Yuma, Arizona. The children are explaining how old they are. (2019)

Howard and members of the Yuma County Sheriff’s Office provide aid to a woman migrant suffering from heat stroke and dehydration. (2021)

Photo Credit: Sheriff Leon Wilmot

Howard speaks with Faustino Landa Badillo, 69, who had previously spent nearly 20 years working in Texas as a day laborer. He carries documents from the 1970’s, including an identification card issued by the Texas Department of Public Safety. (2021)

Howard, his K9, Vait, and rancher Warner Glenn on the U.S./Mexico border outside of Douglas, Arizona. (2021)

Howard assists a family from Honduras who have been travelling for weeks to get to the U.S. border and have voluntarily surrendered to Border Patrol agents. (2021)